Musical symbols convey musical concepts like pitch, rhythm, volume, tempo, and more in a piece of written music. So the first step in learning how to read music is recognizing these basic musical symbols and understanding what they mean. Together, musical symbols form a basic “vocabulary” that is accepted and understood by musicians around the world.

In this lesson, we’ll take a look at the most important musical symbols used in standard notation. This will give you a good foundation if you want to learn how to read music as part of your daily practice routine. So let’s dig in!

The Staff

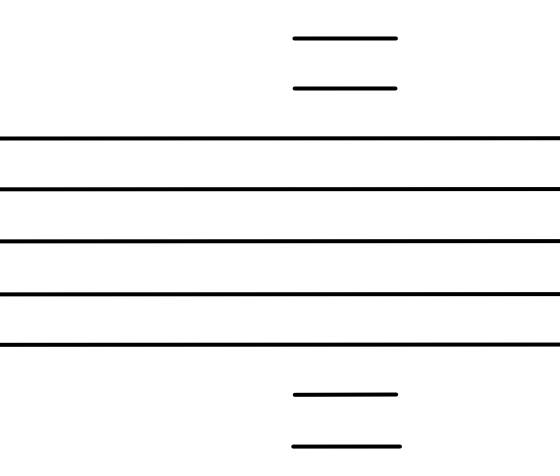

The staff is a set of five horizontal lines upon which all the other musical symbols are placed. Unlike Guitar TAB notation, which uses six similar lines to represent the guitar strings, the lines in standard notation do not represent strings or any other physical object. In contrast, they are abstract symbols used to indicate different pitches, as described below. Here’s what the staff looks like without anything else on it:

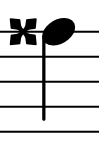

Often, the notes to be played extend outside the five lines and four spaces of the staff. In these cases, ledger lines are used to extend the staff. These are just short lines that create space for additional notes above or below the staff, as shown here.

In this example, two ledger lines are shown both above and below the staff. But more, or fewer, ledger lines can be used, and they can appear only above or only below the staff, as needed.

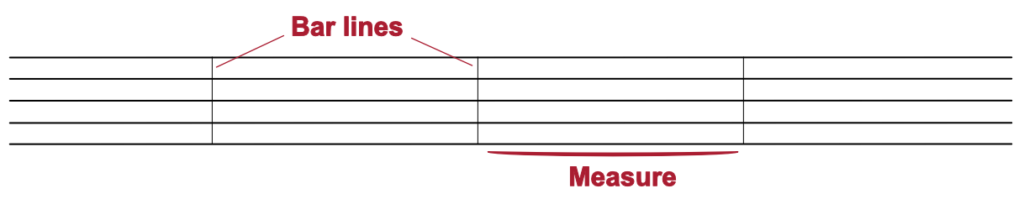

Bar Lines and Measures

Bar lines are vertical lines that are placed on the staff to divide the piece of music into units called measures or bars. For example, this staff contains three bar lines and four measures:

Each measure in a section of music contains a specific number of beats, as defined by the time signature, described below.

Clefs

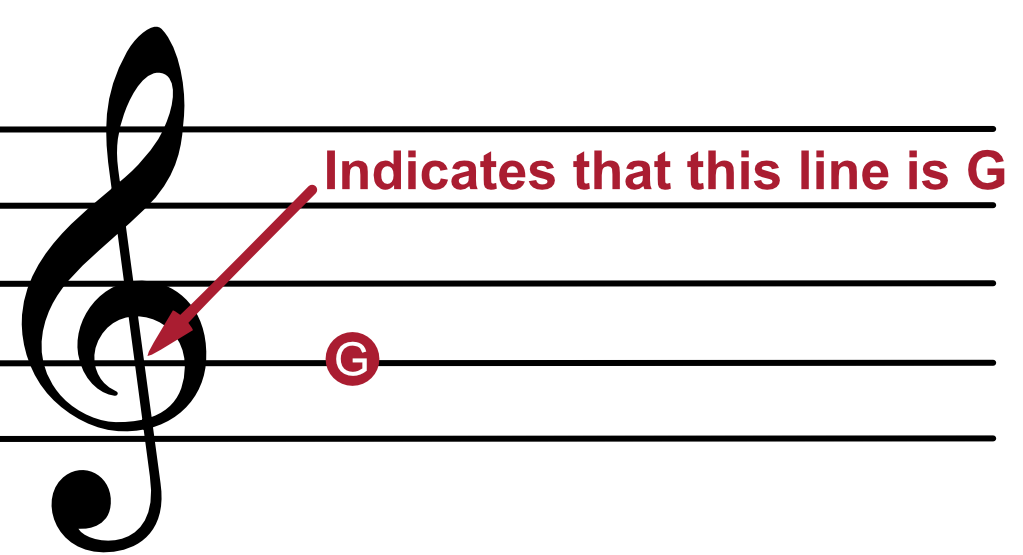

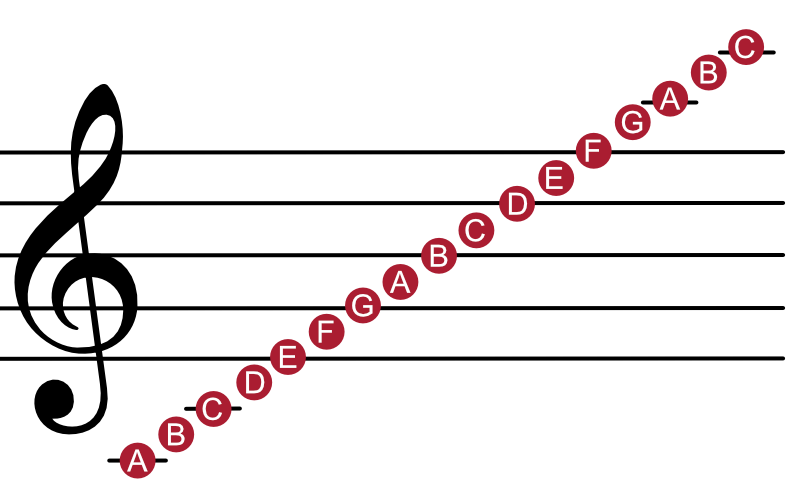

Because different instruments have varying pitch ranges and are tuned differently, the lines and spaces on a staff can be used to represent different pitches. In a given piece of written music, a clef symbol indicates which pitches will be represented by the lines and spaces on the staff.

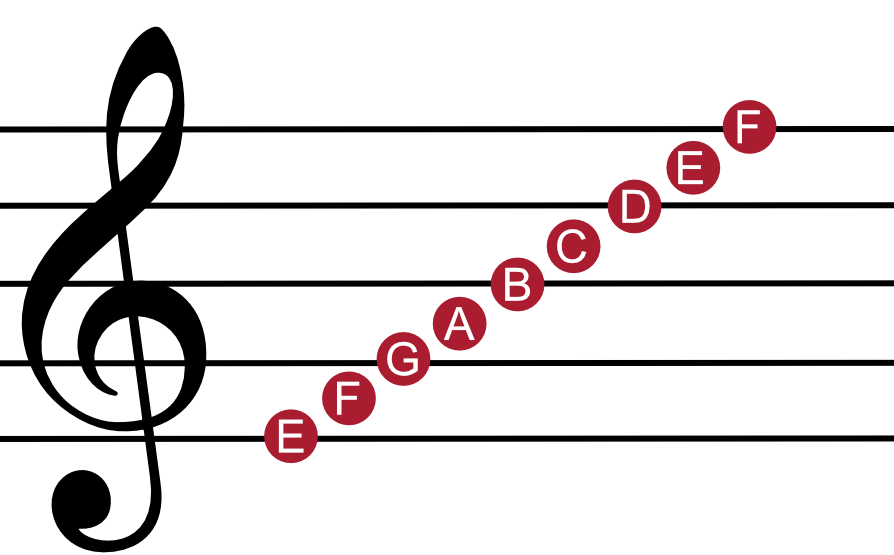

Music written for the guitar uses the treble clef, or G clef. It’s called the G clef because the line that passes through the curl of the clef is used to represent the pitch G:

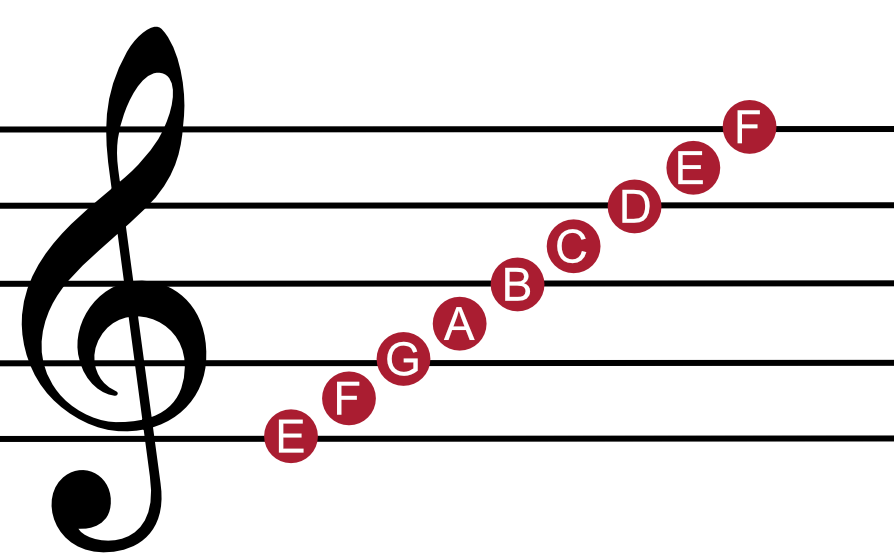

Since the treble clef indicates which note is G, the other notes are derived from that. As shown here, each line or space is one note higher or lower than the line or space next to it:

And if ledger lines are used, as described above, the same repeating pattern continues both above and below the staff, like you see here.

Keep in mind that the notes shown here are correct for the treble clef, but if a different clef is used, the notes will be different. To clarify, the pattern will be the same (it will always be A B C D E F G), but the notes will appear on different lines and spaces.

Other commonly used clefs include the F clef (bass clef)—used for bass instruments like bass guitar, cello, piano (left hand), and more—and the C clef (alto clef), used mostly for viola. But these aren’t used for guitar so I won’t go into details about them here.

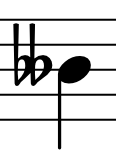

Key Signatures

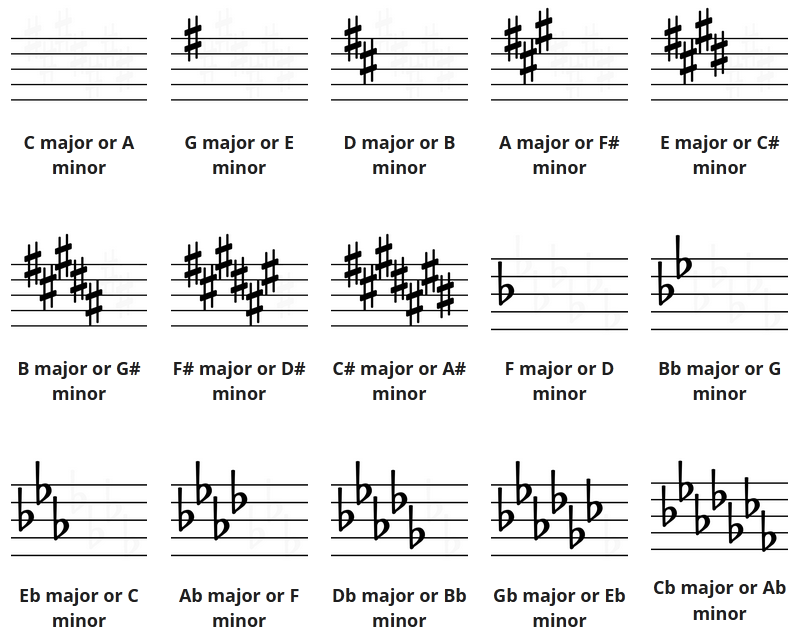

The key signature is the area to the right of the clef that shows what key the musical piece or section is in. This is done by showing a number of sharps or flats (see Sharps and Flats, below). Each specific combination of either sharps or flats indicates a specific key, as shown below. If no sharps or flats are shown, the piece is in C major or A minor.

When a key signature is used, all of the notes in the piece that correspond to a line or space containing a sharp or flat in the key signature are either sharped or flatted (unless otherwise notated, such as with a natural, or double sharp). For example, as shown above, the key signature for the key of G contains one sharp: F. As a result, every F that appears in the piece or section is understood to be F# (unless otherwise notated).

Notes and Rests

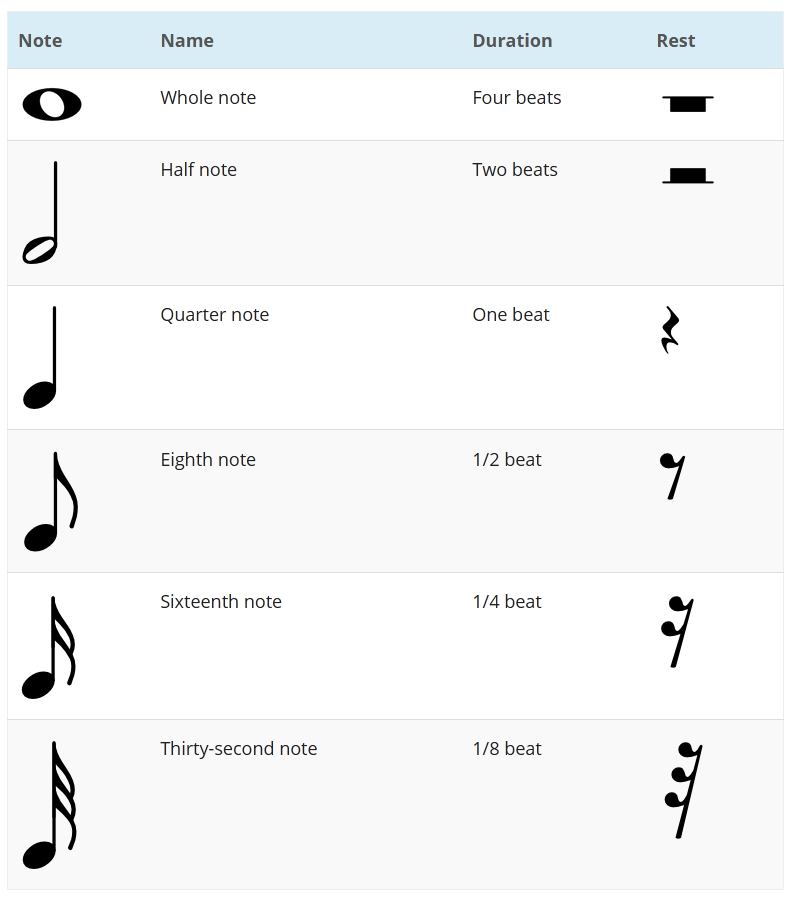

As you probably already know, a note indicates what pitch to play and for how long. You can think of the musical symbols discussed above as the foundation for a piece of music, and the notes as the structure that is built upon that foundation.

For each note, there is a corresponding rest that indicates silence for the same duration. The duration of a note or rest isn’t absolute but is instead relative to the other notes around it, and this depends on the tempo and the time signature of the piece of music. But to keep things simple for now, we’ll stick to the convention of one quarter note = one beat, since that’s the most common usage.

By using a note of a certain value and placing it on a certain line or space on the staff, you can indicate both what pitch to play and how long to play it.

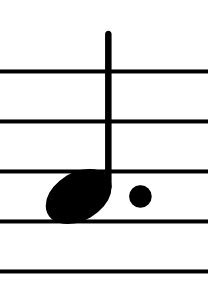

Dotted Notes

When a dot follows a note, the duration of that note is extended by one half of its original duration. So, for example, in 4/4 time, a dotted half note is played for three beats instead of two. Likewise, a dotted quarter note is played for one and a half beats instead of one, like so:

Tied Notes

When notes of the same pitch are tied, the notes are played as one note with a duration equal to their individual durations added together. So, for example, a quarter note tied to an eighth note is played once, with the note sounding for 1 1/2 beats. That is to say, you don’t play each note individually.

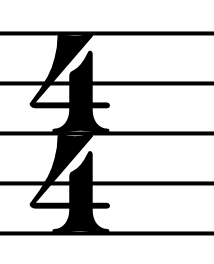

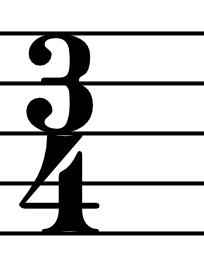

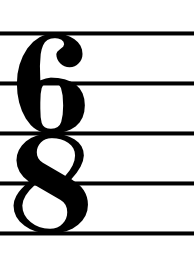

Time Signatures

The notes and rests shown above aren’t fully meaningful unless they are paired with a time signature. Time signatures define the rhythm of a piece of music by doing two things: (1) indicating how many beats appear in each measure and (2) defining which note is equal to one beat.

Most often, the time signature is represented as a fraction, with the numerator showing how many beats per measure and the denominator showing which note to count as one beat. The denominator is shown in fractions of a whole note, so “2” = a half note, “4” = a whole note, and “8” = a sixteenth note. Common examples include the following:

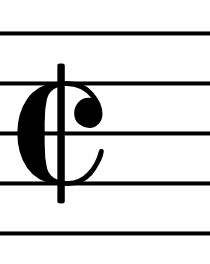

Sometimes, instead of the fractional time signatures shown above, the symbols shown on the right are used to represent common time and cut time, respectively.

Various other time signatures are used as well, including 2/4, 12/8, 7/8, and all kinds of other crazy stuff. However, the vast majority of music that a beginning player will encounter will use one of the time signatures shown here.

Tuplets

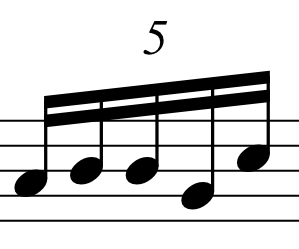

Tuplets provide a way to divide the beat into notes of equal duration in a way that is not consistent with the time signature. For example, in 4/4 time, a tuplet can be used to evenly divide a beat into five notes.

The most common tuplet is the triplet, which divides one or more beats into three notes. Other types of tuplets, including quintuplets and sextuplets, are less common but still widely used. A number above the tuplet indicates the type of tuplet, or the number of equal divisions of the beat.

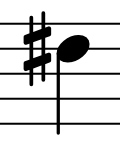

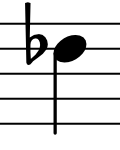

Sharps and Flats

Sharps and flats indicate higher and lower pitches in a piece of music. A sharp raises the note that follows it by one semitone. In contrast, a flat lowers the note that follows it by one semitone. (A semitone is also called a half step and is the smallest pitch interval in Western music.)

As shown in Key Signatures above, sharps and flats are used in key signatures to indicate the predominant key in a piece or section of music. Sharps and flats are also used throughout the piece to indicate deviations from the key signature. When used this way, they are called accidentals.

Other Accidentals

In addition to sharps and flats, a piece of music might also contain naturals, double sharps, or double flats.

Dynamics

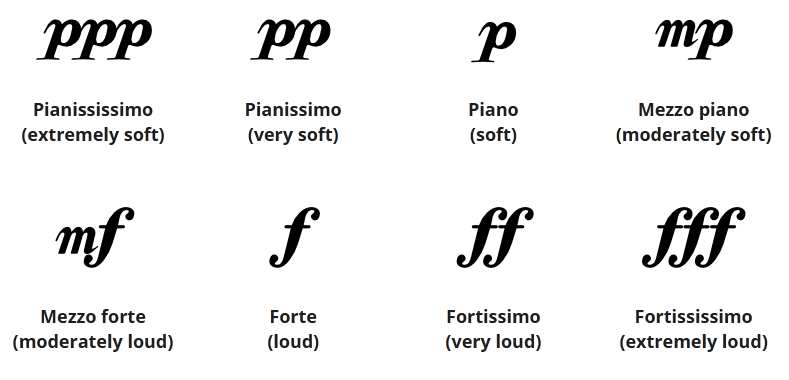

Dynamic markings are used to indicate the relative volume of a section of music. Many different dynamic markings exist but the most commonly used are as follows:

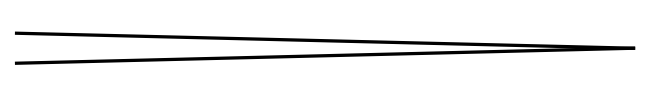

Crescendo and diminuendo marks indicate a gradual increase or decrease in volume:

In addition to the marks shown here, cresc. and dim. are often used to indicate crescendos and diminuendos.

Articulations

Articulation marks indicate how a particular note should be played within a section of music. For example, an articulation might indicate that a note should be played with emphasis, or should be sustained longer than usual. Here are a few of the most common articulation marks:

Conclusion

Although many other musical symbols exist that are not covered here, this lesson contains all the basic musical symbols you’ll encounter in the beginning stages of learning how to read music. Reading music has so many benefits, and is actually fun if you approach it with the right mindset. So I encourage you to take the next step and use this new vocabulary you’ve learned to start learning how to read notes on the guitar.

This is an awesome website this really helped me

Thanks:)

Thanks–I’m really glad to hear that!

very clear