Triads are three-note chords made by stacking two thirds together. Let’s break this down to understand what it means:

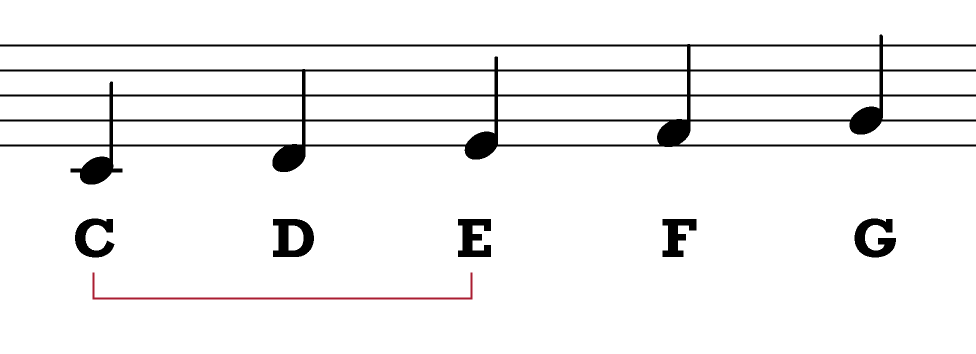

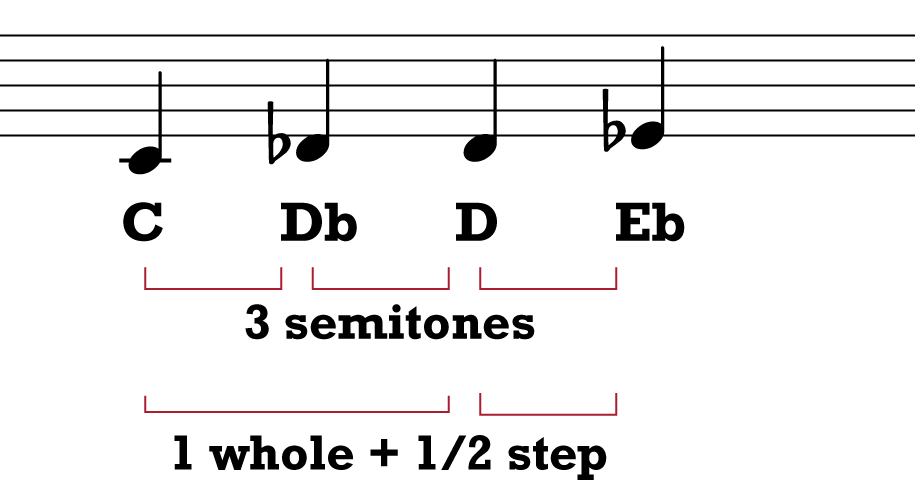

If you already read the lessons on intervals and the chromatic scale, you know that a third is a set of two notes that are two steps away from each other in a diatonic scale. For example, the notes C and E form a third because E is two steps away from C. (C to D is one step; D to E is the second step.)

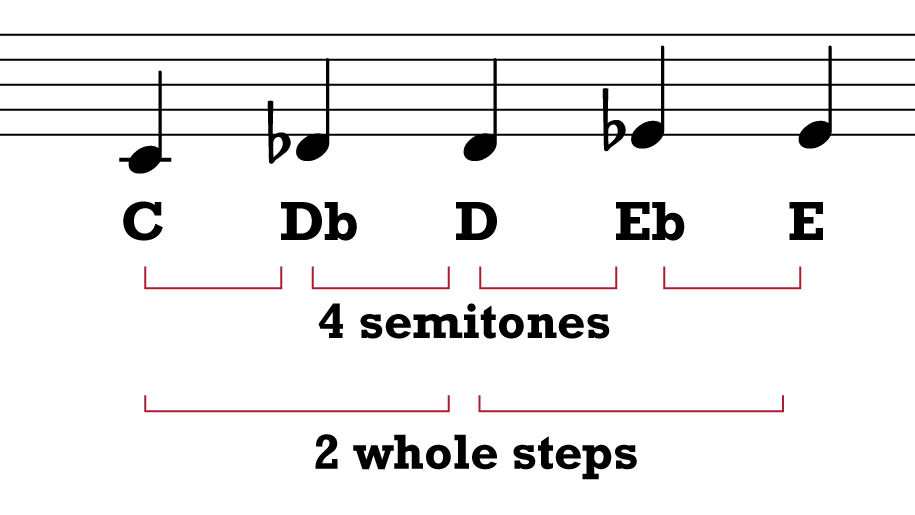

You also know that the two basic types of thirds are major thirds, which span a distance of two whole steps (or 4 semitones), and minor thirds, which span a distance of one and a half steps (or 3 semitones).

Here are two examples:

The Four Types of Triads

So now we know that a triad is made by stacking two thirds on top of each other, and the two primary types of thirds are major thirds and minor thirds.

This gives us four possible stacking combinations, each of which results in a different type of chord:

- Major third + minor third = major triad

- Minor third + major third = minor triad

- Major third + major third = augmented triad

- Minor third + minor third = diminished triad

These rules are the key to understanding why any given chord is called major, minor, augmented, or diminished. Keep the rules in mind as we look at specific examples below.

Building Chords From the Major Scale

Since we know that thirds are two steps away from each other in major or minor scales, we end up with the following convenient fact:

Triads can be built by starting on a note from a diatonic scale and adding every other note until reaching three notes.

Let’s apply this to the major scale to see the chords we wind up with.

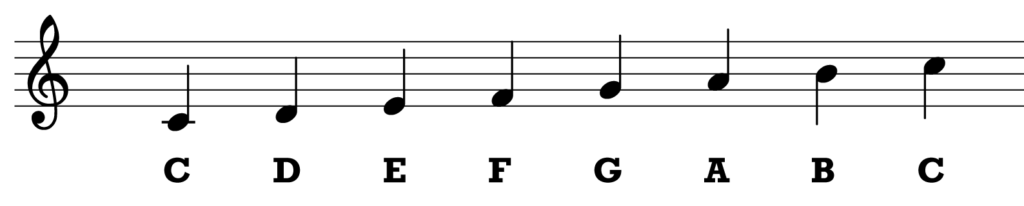

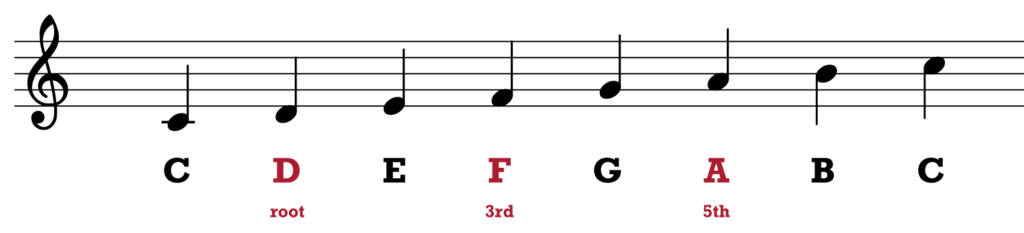

Here’s the major scale in C:

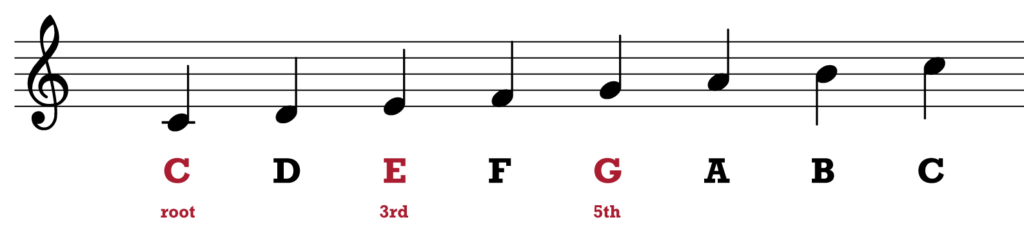

If we start on C, and then take every other note, up to a total of three notes, we get C – E – G:

You’ll notice that the three notes of a triad are labeled the root (the note the triad starts on), the 3rd, and the 5th.

So C – E – G is a C triad made up of two thirds (C – E and E – G). But what kind of triad is it? To figure that out, we need to see what kinds of thirds C – E and E – G are.

We already saw from above that C – E is a major third, because there are 4 semitones between C and E. And if we count from E to G, we see that they are separated by 3 semitones, which makes E – G a minor third:

So we have a major third plus a minor third. Let’s look again at that list of stacking combinations, especially the first one:

- Major third + minor third = major triad

- Minor third + major third = minor triad

- Major third + major third = augmented triad

- Minor third + minor third = diminished triad

So now we know that C – E – G is a C major triad (or C major chord).

This may seem like a lot of work, when we could easily google “C major chord” instead and find out it’s C – E – G. But stick with me here because, if you know how chords are built, you won’t have to memorize seemingly random chord spellings. Instead, you’ll understand how those chords are made and how they fit together in a key. And that will make memorizing them, and knowing how to use them, a lot easier.

Let’s move on to the next note in the scale, D, to see what chord that gives us:

If we start on D and then take every other note up to a total of three notes, we get D – F – A:

If you count the distances between the notes on the chromatic scale, you’ll find that the distance from D to F is 3 semitones, or a minor third, and the distance between F to A is 4 semitones, or a major third. Now we have a minor third plus a major third. Here’s our list of combinations again:

- Major third + minor third = major triad

- Minor third + major third = minor triad

- Major third + major third = augmented triad

- Minor third + minor third = diminished triad

So this tells us that D – F – A is a D minor triad (or D minor chord).

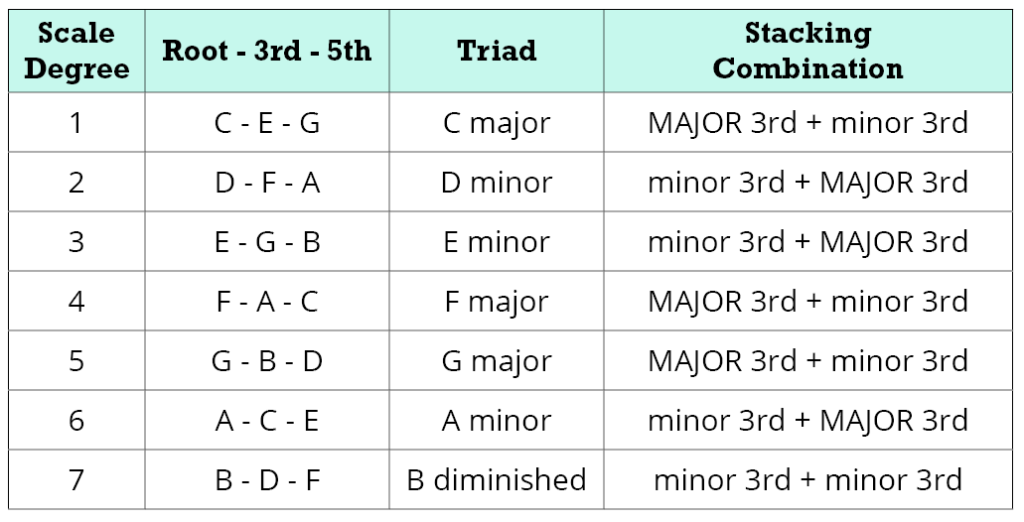

So far we’ve gone through this process with the first two notes of the major scale. If we were to do it for all the notes in the scale (which I strongly recommend you do), we’d come up with the following chords in the key of C:

Diatonic Chords

The table of C major chords above can be generalized so that we can see the diatonic chords for any major key. Diatonic chords are the chords that are built using only the notes from a particular key, just like we did above.

The following table lists the type of chord that is built on each step of the major scale in any key. Also shown are the Roman numerals that are used to refer to these chords. Uppercase letters (like IV) indicate a major chord and lowercase letters (like ii) indicate a minor chord. The diminished chord is represented using lowercase letters plus the ° symbol:

When talking about chords within a particular key or chord progression, musicians often refer to the chords by their position/scale degree. They’ll refer to the chord built off the 1st scale degree (the tonic chord) as the “one chord”, the chord built off the 2nd scale degree as “the two chord”, and so on.

Also, they know the quality of each chord in the key. (A simplified definition of chord quality is whether the chord has a major, minor, diminished, or augmented sound.) So, for example, they know that the “two chord” is minor. And they know that the “four chord” is major. And when you memorize the above chart, you’ll know this too.

Note that the augmented triad that I referred to above (major 3rd + major 3rd) doesn’t appear naturally when creating triads from the major scale (or any diatonic scale, for that matter). However, augmented chords are often used in classical music and jazz to add a feeling of tension or suspense.

Rules for Making Triads

Knowing how triads work will help you identify chords and create alternate fingerings as needed. To do this quickly, you just need to know a few simple rules that follow from the information presented above.

We know that a major triad is a major 3rd + a minor 3rd, giving us root – 3rd – 5th. And a minor triad is a minor 3rd + a major 3rd, giving us root – flat 3rd – 5th. The general rule is this:

To change any major chord to a minor chord: lower the 3rd by one half-step.

We could go through this exercise with the other types of triads as well but, to keep things simple, here are all the rules, which you should definitely memorize:

| To change from this chord: | To this chord: | Do this: |

|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | Lower 3rd a half-step |

| Major | Augmented | Raise 5th a half-step |

| Major | Diminished | Lower 3rd and 5th a half-step |

These rules also work in reverse. So, for example, to go from a minor chord to a major chord, raise the 3rd a half-step, and so on:

| To change from this chord: | To this chord: | Do this: |

|---|---|---|

| Minor | Major | Raise 3rd a half-step |

| Augmented | Major | Lower 5th a half-step |

| Diminished | Major | Raise 3rd and 5th a half-step |

These rules are really important and get applied in so many different ways on the guitar. For example, they can help when soloing. Let’s say you’re soloing over C major, and targeting the notes in the C major triad: C, E, and G. If the backing chord changes to C minor, you’ll know that E (the major 3rd) will no longer sound right and you’ll need to target Eb (the minor 3rd) instead.

These rules can also be very helpful in quickly finding triad fingerings on the guitar fretboard, which we’ll look at next.

Playing Triads on the Guitar

This section is less about triad theory and more about applying it to the fretboard, but I think it’s important to include here because practicing these shapes and their variations will help you memorize the rules of triad creation.

If we look at the first three strings of the guitar, the triad for any major chord can be played using three different shapes. The different shapes for a given chord each contain the same three notes, but they appear in a different order in each shape. (In other words, they are different inversions of the chord.)

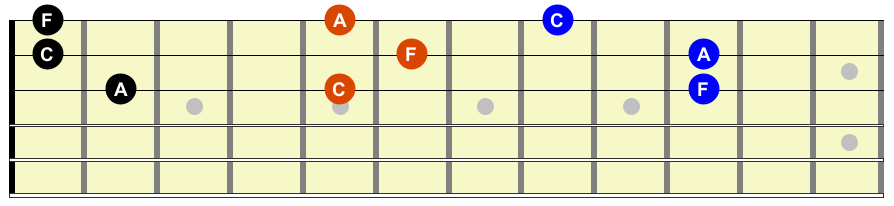

Here’s an example, showing three triads shapes of F major:

As noted above, each shape contains the three notes of the F major triad: F, A, and C. Here we can see where the root, 3rd, and 5th are located in each inversion:

These are the three major triad shapes on the first three strings. (The Guitar Essentials e-book provides a handy reference for the triad shapes for each of the basic beginner chords.) If we combine this knowledge with the rules for making triads shown above, we can derive the corresponding minor triad shapes.

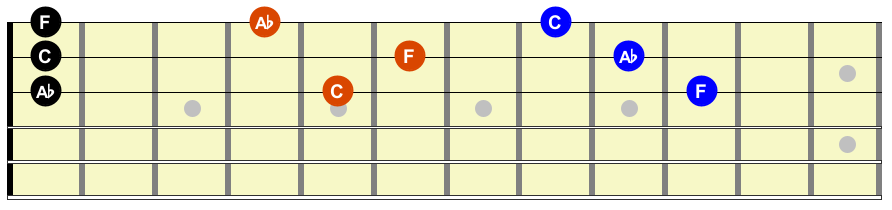

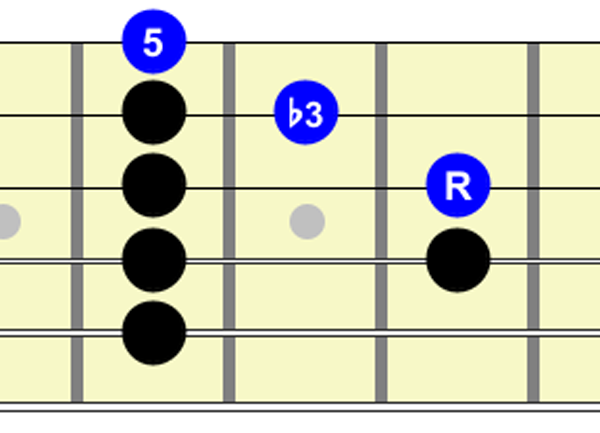

Remember, to go from major to minor, we need to lower the 3rd by one semitone, or one fret. So we lower each A (which is the 3rd of the F-A-C triad) to an Ab. That leaves us with the following shapes:

As before, let’s look at the intervals to show how we now have a root, flat 3rd, and 5th in each of our minor triad shapes on the first three strings.

If you already know barre chords, you might notice that these major and minor triad shapes are the top three notes of larger chords, including 6-string and 5-string barre chords. For example, this major triad is the top three notes of the “E-shape” barre chord:

And this minor triad is the top three notes of the “A-minor-shape” barre chord:

The major and minor triad shapes are the most important ones to memorize. But we can easily derive the diminished triad shapes as well. Remember that a diminished triad is root – flat 3rd – flat 5th so, to make them, you just have to take the minor triads and lower the 5th an additional fret. Here are the shapes for the B diminished triad:

Practice

This is a lot of information to take in but triads are such an important topic that it’s really worth taking the time to both learn them and practice them. Here are some ideas to help incorporate your new knowledge of triads into your practice routine:

- Pick a key (I suggest starting with G major) and write down the major scale for that key. Ideally, you should build the major scale yourself using the pattern described in the major scale theory lesson (W – W – H – W – W – W – H), but you can also just google it.

- Starting with the first note, create the triad for that key as described above: by taking that note as the root, and then taking every other note of the scale, until you have three notes. Starting on G, this gives you G B D.

- Referring to the scale degree chart above, write down whether this is major or minor. Since G B D started on the first note of the major scale, it’s major. So write down I: G B D – G major.

- Now repeat steps 2 and 3, starting with the second note of the major scale (in this case, A). If you do it correctly, you should wind up writing: II: A C E – A minor.

- Repeat these steps for all the remaining steps of the scale, essentially creating your own table similar to the tables shown earlier. You’ll have seven rows in your table, one for each diatonic triad of the major scale.

- Using the triad shapes shown above, play the triads listed in your table on the guitar. For each triad, try to find all three shapes shown in the diagrams.

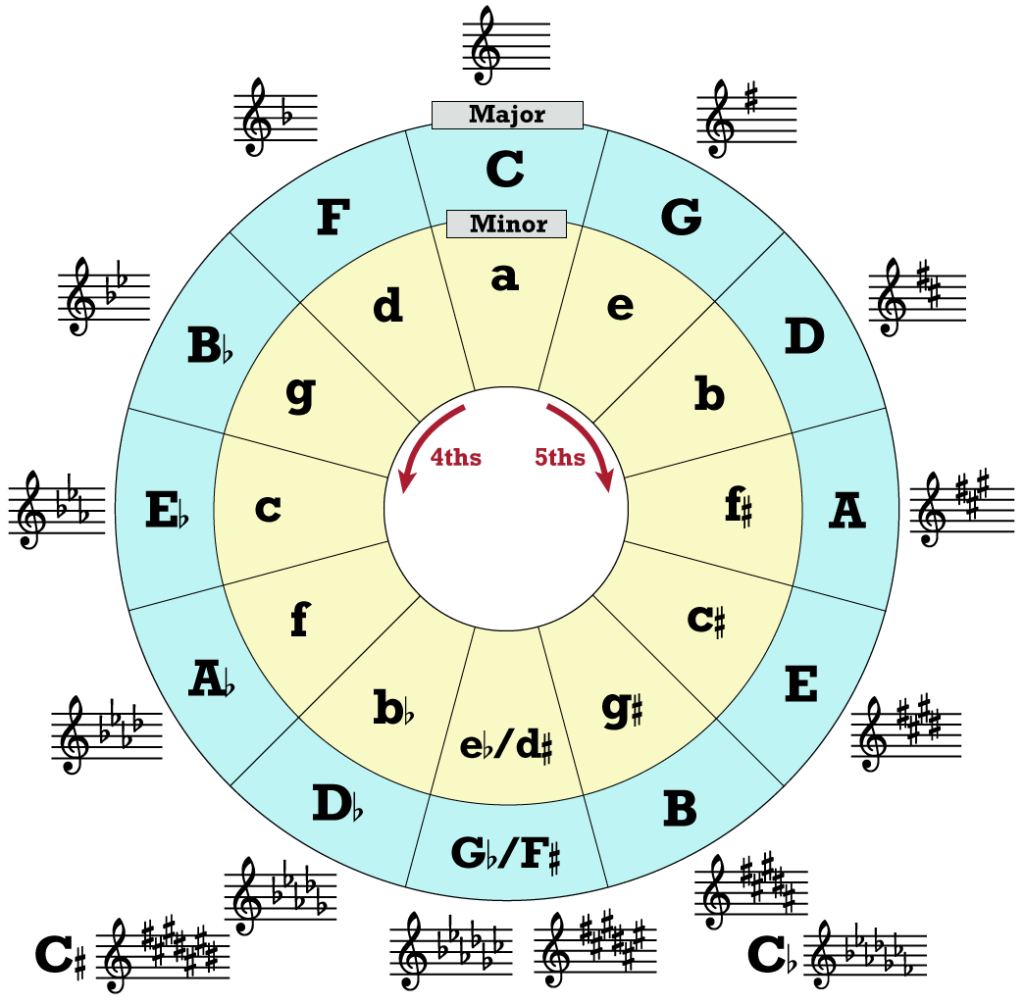

This should be good for one practice session. The next time you practice, you can pick a different key and repeat the whole exercise. To select keys, I suggest going around the circle of fifths. In that case, after G major, you’d work on D major, then A major, and so on:

Work your way around the circle of fifths, picking a new key each practice session

Although it might seem tedious to repeat this exercise in all the keys, it’s a very effective way to gain an understanding of how triads are made and how different triads fit together within a key. Take the time to incorporate some triad study into your daily practice, and you’ll find that it will open up new possibilities on the guitar and will help broaden your musical understanding.