Many guitarists want to be able to go beyond just strumming chords and want to understand the music theory behind what they’re playing. But they’re not sure where to start. Common questions are “What should I learn first?”, “How do I know what scale to play?”, and “How can I identify chords?”

All of these questions are easy to answer but they require a little bit of basic musical knowledge first. Not a lot, I promise. But it’s important to know some key concepts to answer the larger musical questions that beginners often have. Think of it as learning a foreign language: before you learn simple sentences, you should first learn some of the most common vocabulary words.

You’ll learn the following concepts in this lesson:

- Notes

- Sharps and flats

- The chromatic scale

- Whole steps and half steps

Keep in mind that that I’m not going to into thorough, exhaustive detail about each concept because then the lesson would be really long and would read like an encyclopedia article. I’m just going to explain the parts that are relevant to guitar players who are new to music theory. For more details about musical notation, check out the Musical Symbols lesson.

Musical Notes

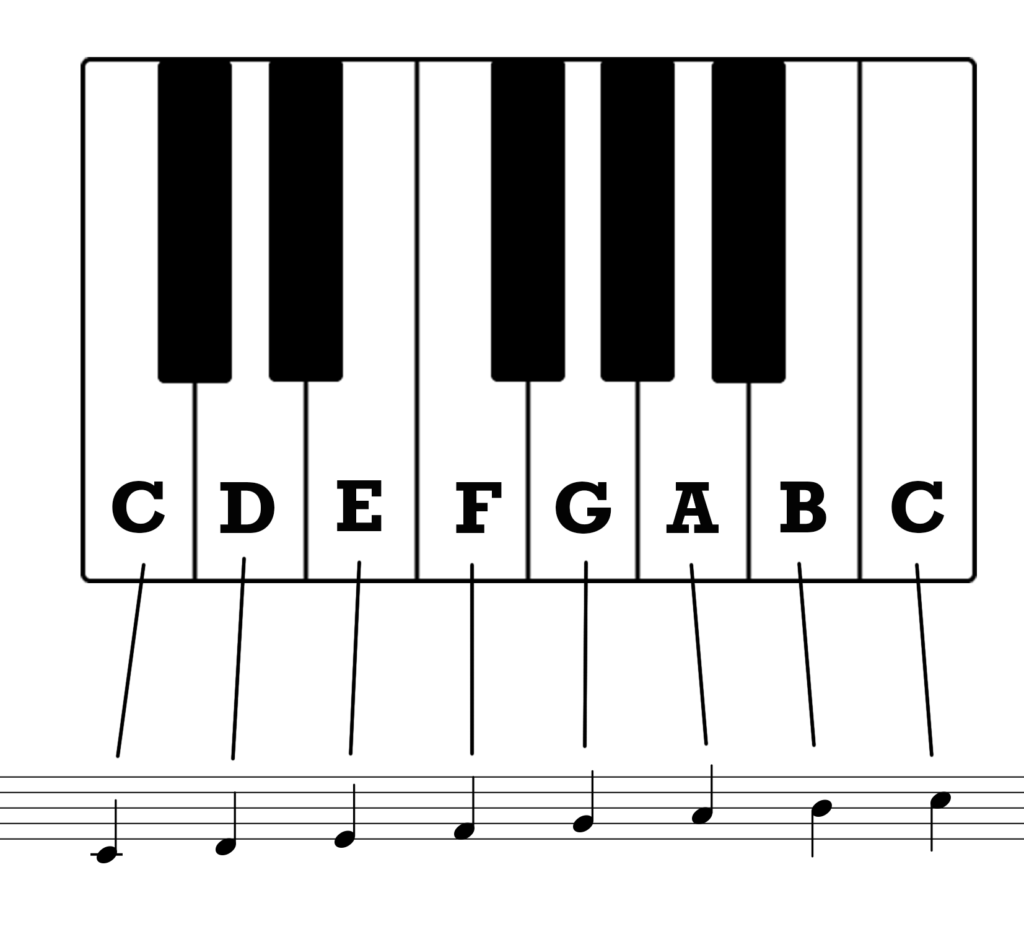

Some of this may be obvious, but let’s start at the very beginning to make sure nothing gets missed. First, let’s look at what a note is. A musical note is a symbol that indicates what pitch to play and how long to play it. Notes are placed on the five-lined musical staff and, together with the clef, let the musician know what notes to play.

All of the notation in this lesson assumes we’re using the treble clef, which is the clef used for guitar. The clef tells you what notes are indicated by the lines and spaces on the musical staff. Other instruments use other clefs, like bass clef or alto clef, in which case the lines and spaces on the staff indicate different notes. But all we have to worry about for the guitar is the treble clef, which I explain here.

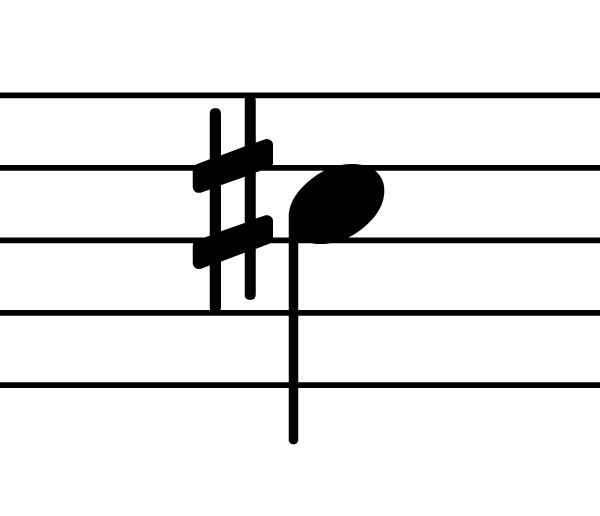

If you put the eight notes from a major scale (“Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do”) on a musical staff, it looks like this:

This happens to be a C major scale, so the notes are C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. Note that, in the key of C, this represents all the white keys on a piano:

This is all pretty easy so far, right? Well let’s dig into just a few more concepts that, when you understand them, will make things like chords and scales much easier going forward.

Sharps and Flats

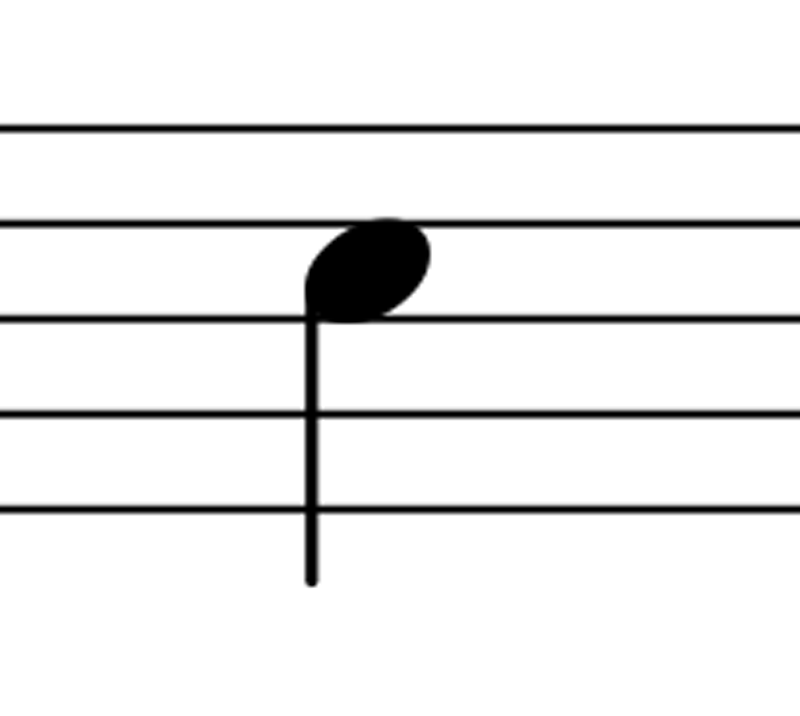

When a sharp is placed in front of a note, it indicates a pitch one semitone higher than the normal pitch. See Whole Steps and Half Steps below for the definition of a semitone. For now, just think of it as the next position (up or down) on the scale.

For example, this notation indicates that the musician should play C# (C sharp). Note that we’re using the same C note that we used above, but we added a sharp symbol in front of it.

When a flat symbol is placed in front of a note, it indicates a pitch one semitone lower than the normal pitch.

So, for example, the note to play here is Db (D flat). We have a D note with a flat symbol in front of it.

One important thing to understand about sharps and flats is that the same note that you hear (the same pitch) can be notated in different ways. For example, the two notes shown above (C# and Db) are the same pitch—the note that you hear is exactly the same. The two different ways of notating it are basically saying “move up a semitone from C” or “move down a semitone from D”. In either case, you wind up with the same note. More on this below, as we move on to the chromatic scale.

The Chromatic Scale

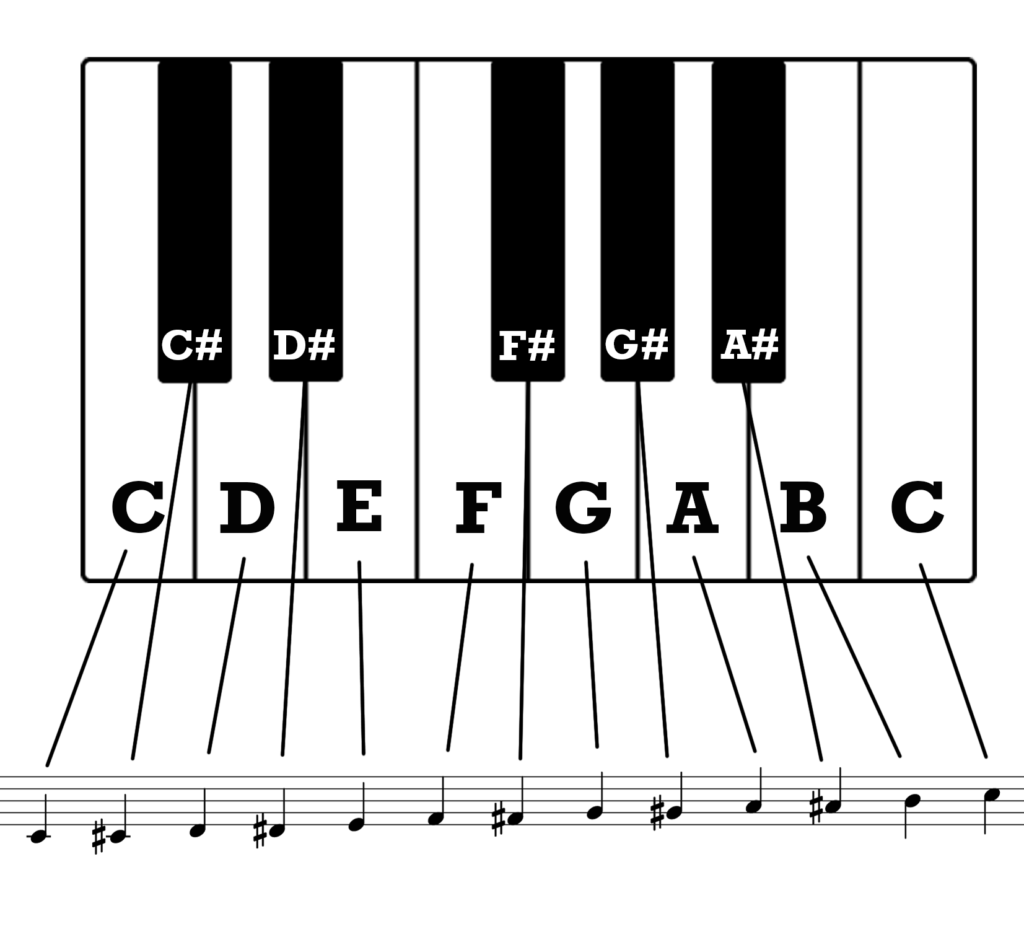

The major scale that most of us are familiar with uses 7 notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B. Usually, when playing scales, we repeat the root note at the end (one octave higher), resulting in eight notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. As noted above, in the key of C, these are the white keys on a piano. But there are other available notes as well, and we get them if we add in the black keys too. This gives us a scale with 12 notes, called the chromatic scale:

C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C

The chromatic scale represents all the possible notes we have to work with in Western music. (Other musical traditions like those from India and other Asian cultures, as well as some Western avant-garde music, use so-called “microtonal” scales, with more than 12 notes.)

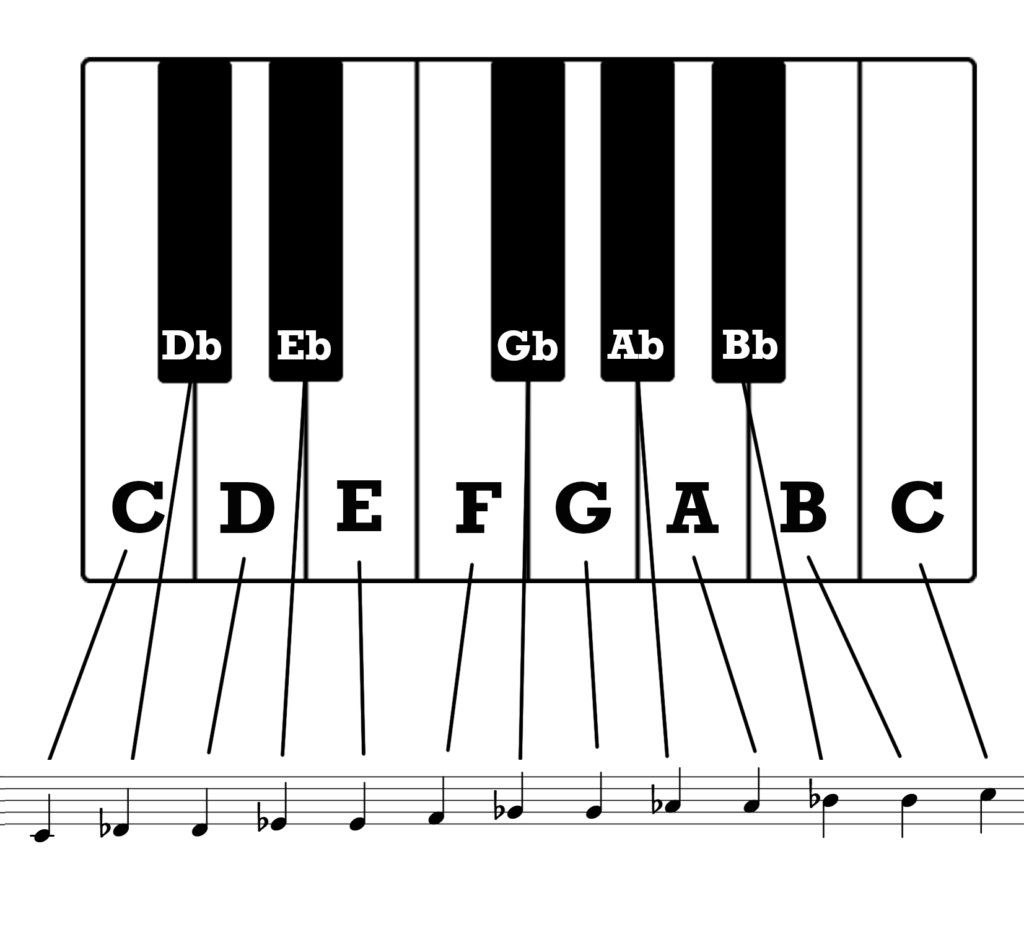

The chromatic scale can be written using sharps or flats, or both. Here’s the exact same chromatic scale shown above, but this time using flats instead of sharps:

C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B C

Whether to use sharps or flats in any given situation depends on a lot of factors, so I won’t go into that now. Just know that multiple names are used for the same notes. For example, F# is the same exact note as Gb. It’s just two different ways of referring to the same note.

You’ll notice that the scale goes directly from E to F and directly from B to C. In other words, there is no E# or B#. Likewise, there is no Fb or Cb. No need to worry right now about why this is the case; it’s just something you need to remember.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the chromatic scale can start and end on any note within the scale. That is, it doesn’t have to start and end on C. The notes within the scale remain exactly the same. So, for example, the G chromatic scale looks like this:

G G# A A# B C C# D D# E F F# G

Let’s take a look at how the C chromatic scale looks on the piano keyboard. The first image shows the chromatic scale using sharps between the natural notes:

And here’s the same scale using flats instead. Remember, both scales are the same; we’re just using different names for some of the notes:

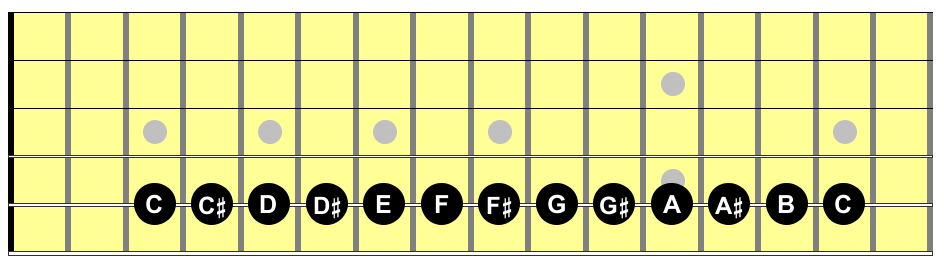

And since we are, after all, mostly interested in the guitar, let’s take a look at the same chromatic scale on the guitar fingerboard, starting on the 3rd fret of the A string:

This might not be the most exciting topic in the world, but it’s really important. So study that chromatic scale and work on memorizing it. It will be incredibly helpful in understanding how chords and scales work.

One last thing to cover before we wrap up this lesson: whole steps and half steps. Read on…

Whole Steps and Half Steps

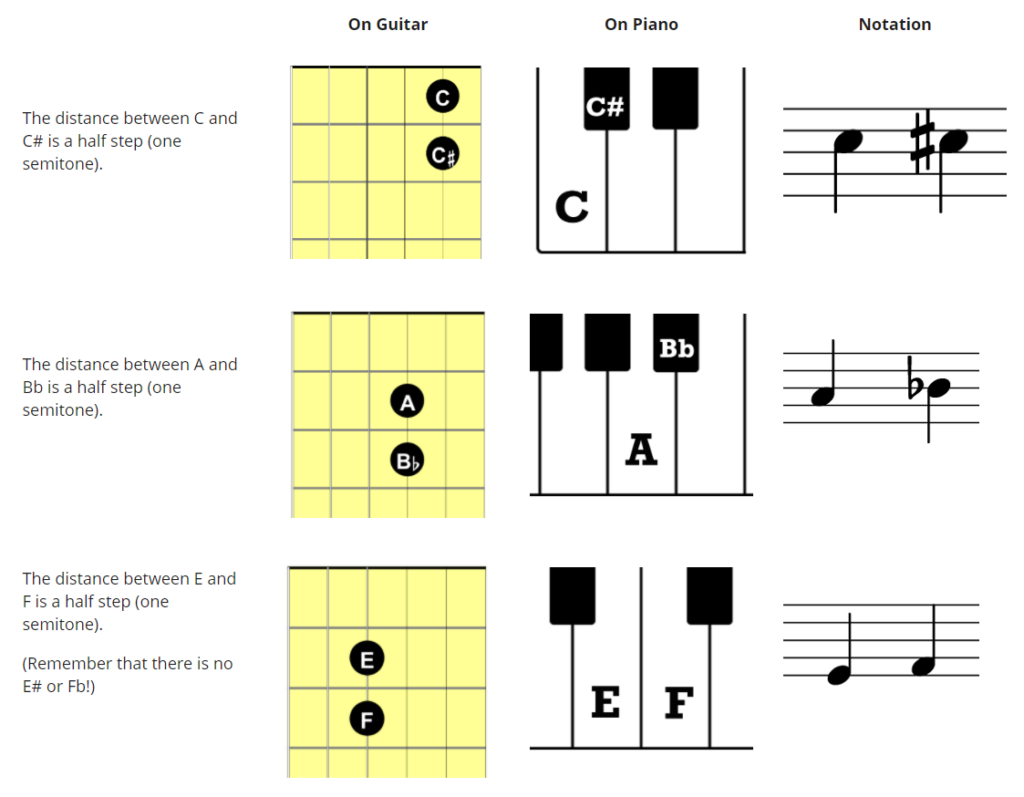

The last thing we’re going to look at involves the distance from one note to another. I’ve already used the term semitone a few times above. Now let’s dig into that some more. The distance from one note to the note next to it on the chromatic scale is called a half step or a semitone.

The important thing to remember for the guitar is that each fret is one semitone (one half step) away from the note next to it.

Let’s look at some examples:

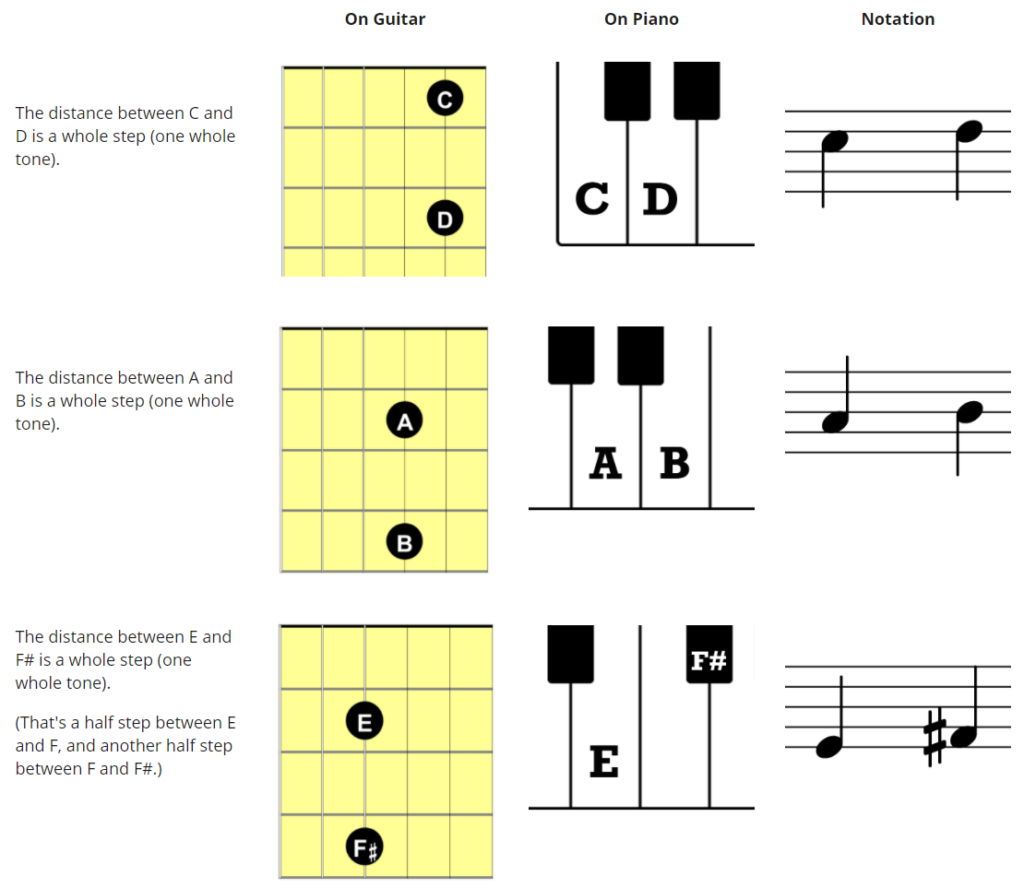

So much for semitones and half steps. The other unit of musical distance we want to look at is called the whole step or whole tone. A whole step is the distance from one note to another note two positions away from it on the chromatic scale. As you might have guessed, two half steps = one whole step. Or, put another way, two semitones = one whole tone.

On the guitar, the distance of a whole tone is represented by two frets.

Once again, let’s check out some examples:

Practice

So now you know the first few building blocks of music theory, including the chromatic scale. Now it’s time to practice it so you can actually start using it in your playing. Here’s what I suggest you do:

- Start With C: Play a C on the guitar. You can start with any C you can find. For example, there’s a C on the 3rd fret of the A string, one on the 5th fret of the G string, and one on the 1st fret of the B string.

- Ascending C Chromatic Scale: Now, on the same string, move up one fret at a time and say the name of each note that you play. So, for example, play one fret higher and say out loud “C sharp.” Then move up another fret and say out loud “D”. Then move up another fret and say out loud “D sharp”. Do this all the way up the string until you reach C again. Your final C should be exactly 12 frets higher than your original note. Try to say each note without looking at the scale shown in this lesson. But if you get stuck, just look at the scale and find your place. Remember the “special” steps between E and F and between B and C.

- Descending C Chromatic Scale: Do the same thing starting at the high C note (the one you ended on at the end of Step 2), but this time move down one fret each time. Use flats this time. So, for example, move down one fret from C and say out loud “B”. Then move down another fret and say out loud “B flat”, and so on. This will help you internalize the idea that sharps can be flats and flats can be sharps.

- Ascending and Descending Chromatic Scale Starting on Different Notes: Do the same exercise described in Steps 1-3 but start on different notes—don’t start on C. Try going from A to A, or from Bb to Bb. The notes in the chromatic scale are the same, regardless of what notes you start and end on.

- Chromatic Scale Across Multiple Strings: Try the same exercises described in Steps 1-4 but, this time, when you get to a note that is the same as one of the open strings, move to that string and continue the scale on that string. For example, if you start with C on the 3rd fret of the A string, when you get to the 3rd step of that chromatic scale (D), play that D on the open 4th string (which is the D string). Then continue going up the scale one fret at a time on the 4th string. When you get to the G on the 5th fret of the 4th string, play that G on the open 3rd string (which is the G string) and continue up on that string until you reach the final C. This will help you learn how the notes move up not only horizontally, along one string, but also vertically, across multiple strings.

Next Steps

That’s it for part one of this series. It’s all pretty basic stuff but, as I’ve said a few times now, it’s really important for understanding everything that comes after. The next few lessons in this series will cover the following topics, and when you’ve gotten through all of them, you’ll have a solid understanding of music theory as it relates to the guitar. And you’ll be able to apply this knowledge when figuring out songs, soloing over chord changes, writing a song, etc. The next building blocks that we’ll look at in subsequent lessons are (in rough order):

- Intervals

- Major and minor scales

- Modes of the major scale

- Triads (three-note chords)

- Seventh chords (four-note chords)

These are the main area of focus but I’ll also delve into some other related topics like the circle of fifths and additional scales.

Take it one step at a time and you’ll get all of this easily, and you’ll be a better guitar player for it. See you in the next one.